Before "Lake Street":

Indigenous Communities

The area we now know as Minneapolis has been, and continues to be, home to many indigenous communities. Prior to European settlement, Dakota and Objibwe people, among others, had lived in and traveled through the area for hundreds or thousands of years. On Lake Bde Maka Ska, a Dakota agricultural community known as Ḣeyate Otuŋwe existed from 1829 to 1839, and is now commemorated with artwork along the south side of the lake.

Throughout this era, indigenous people were pushed away from the land they called home through broken treaties and government-sanctioned aggression. Due to this, many of the remaining stories told about Lake Street are centered on the experience of the immigrants who shaped Lake Street in new ways over the decades.

However, indigenous communities are still core to Lake Street and its surrounding neighborhoods, especially in the Phillips communities. Nearby Franklin Avenue has become widely recognized as a Native American cultural corridor. Several important Native-led organizations are now located along the Lake Street corridor, including Division of Indian Works, Migizi Communications, and First Nations Kitchen. Lake Street is indigenous land, and native artists and entrepreneurs continue to play a critical role in shaping Lake Street’s identity.

Late 19th Century:

Early Immigration & Transportation Infrastructure

When Minneapolis was formally established as a city in 1856, what is now Lake Street was about a mile beyond the city’s southern boundary and was mostly farmland. The small but growing city was mainly inhabited by former Canadians and Americans from the east coast, most of whom lived closer to the river. In the 1870s, huge waves of Scandinavian immigrants started immigrating to Minnesota, along with smaller numbers of Germans, English, Irish, and Greeks, and residential development began expanding south of downtown.

As the street grid began to develop, Lake Street was created and named for the lakes it connected to on its west end. The lakes were a major destination for residents of Minneapolis seeking recreation on the trails and beaches established by the newly-created Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board, and entrepreneurs capitalized on this demand by offering steamboat cruises and tourist hotels.

Lake Street was solidified as a commercial hub as the result of some key infrastructure investments. In 1881, the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad corridor was built just a block north of Lake Street, and brought manufacturing, industry, and wholesale goods to the area. In 1888, Lake Street was chosen as the route for a bridge that linked Minneapolis and St. Paul, establishing it as a critical route for inter-city commerce. And as a love for bicycling swept the nation in the late 1880s, Lake Street was designated as a bicycle route and was a popular connection between popular destinations.

Early 20th Century:

Identity & Commerce

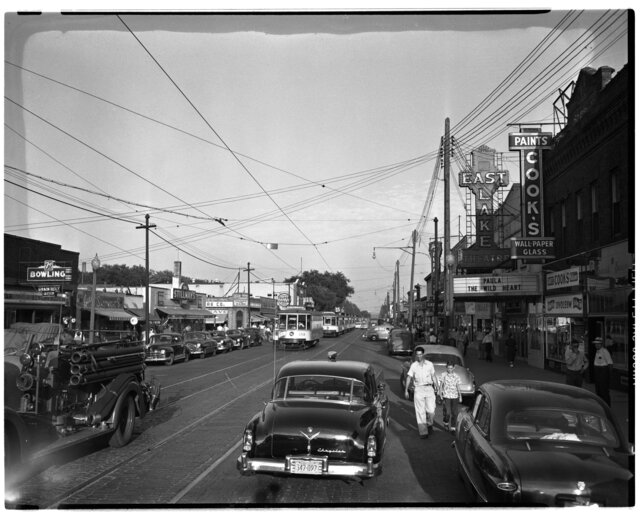

By the turn of the century, various key intersections along Lake Street were connected to downtown Minneapolis via a number of streetcar lines, and in 1905, Lake Street itself received a prominent streetcar line, one that crossed into St. Paul. Streetcar development and real estate development acted hand-in-hand, and nearly all of today’s prominent commercial corridors were established first as streetcar corridors.

As Minneapolis grew, Lake Street became a prime target for new commercial activity, led by waves of new immigrants. While many early Scandanavian-owned businesses are gone, a few remain, including American Rug Laundry, Schatzlein’s Saddle Shop, Ingebretsen’s Gifts & Meat Market, and Soderberg’s Florist. A large influx of Greek immigrants also started businesses like Bills Imported Foods and It's Greek to Me, which today continue to anchor the Lyn-Lake intersection.

Along the rail lines that ran along and through the street, a series of manufacturing businesses developed, most prominent of which was the massive Sears building near Chicago & Lake, along with the sprawling Minneapolis Moline tractor company near Lake & Minnehaha. Manufacturing companies like Smith Foundry and Bituminous Roadways who developed along the railroad continue to operate today. As residential and commercial uses grew up around the railroad, conflicts between trains and other users increased, and by 1910 the railroad was ordered to dig a trench so that the train would be below street grade - the second largest public works project in state history at that time.

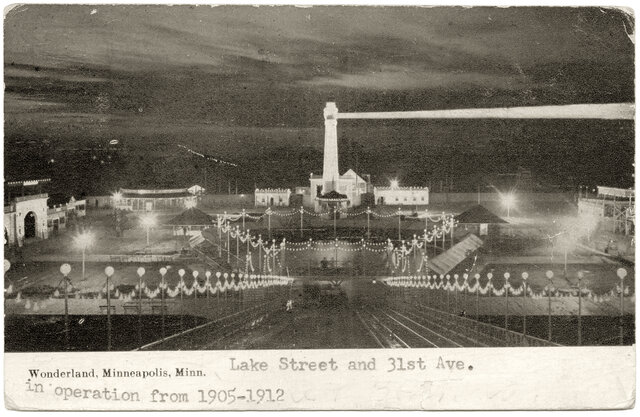

Lake Street was also a destination for entertainment and recreation. At 31st and East Lake, Wonderland Amusement Park brought fantastic and strange attractions that drew huge crowds. Over on the west end of Lake Street, the area surrounding the lakes served as a major destination for day trips and shopping. Business owners in this era started an effort to re-brand the Lake Street & Hennepin Avenue area as “Uptown,” and the iconic Uptown Theater signage helped solidify the area’s name, although it would take decades to become universal.

Late 20th Century:

Suburbanization & Disinvestment

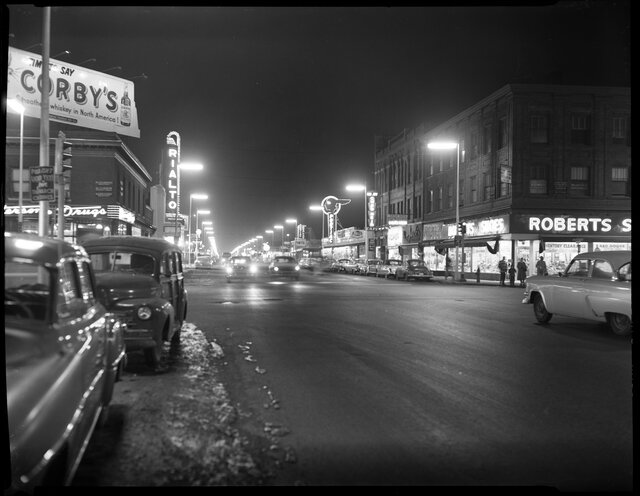

The second half of the 20th century saw major transformation as American cities, including Minneapolis, changed to accomodate and enable the ubiquity of the personal automobile. Decreasing transit ridership led to the replacement of streetcars by buses in 1954. Massive federal investment in the development of the interstate highway system in the 60s and 70s carved up neighborhoods, creating a clear demarcation between neighborhoods that would reinforce class and racial segregation for decades to come.

The expansion of car ownership, and increased personal reliance on cars, led businesses to adapt by courting drivers. New developments mimicked the form of suburban businesses by building large parking lots, the most iconic of which is the Kmart that closed off Nicollet Avenue from Lake. The empty lot left by the departure of Minneapolis Moline near Hiawatha and Lake was filled by Target and Cub Foods.

Car culture was also embraced among several small businesses. Drive-through fast food joints like Porky’s were popular stops for people cruising along Lake Street. Dozens of auto shops like Starr Auto popped up along the corridor to serve the new demand. Still, many businesses suffered or closed as more residents (especially wealthy and white residents) moved out to the suburbs. As vacancies expanded, many older buildings were torn down to make room for parking, and Lake Street started to become defined among many by the increasing and racialized concentration of poverty.

Lake Street Council was founded in 1967 amidst this change as an effort to help support and maintain the businesses that did stay on Lake Street. Many other nonprofit community organizations grew to meet the increasing need in this era, including Little Brothers - Friends of the Elderly, Metropolitan Consortium of Community Developers, and Urban Ventures.

Despite what many described as a challenging time for the corridor in the 80s and 90s, entrepreneurs continued to invest in Lake Street, including a growing number of Mexican and other Latinx immigrants. In 1997, a group of immigrant entrepreneurs formed Mercado Central, a cooperative marketplace at the intersection of Lake and Bloomington. Major businesses like La Loma Tamales, Taqueria La Hacienda, and La Perla Tortillas found their start in Mercado Central, and with their help Lake Street entered a new era.

Early 21st Century:

New Immigration & Investment

In the early 2000s, Lake Street took a turn as a series of new investments by individual entrepreneurs, non-profit developers, major institutions, and public agencies brought transformative change to the corridor.

The towering Sears building, abandoned since the mid-90s, was revitalized into a complex that included the Midtown Global Market, Allina Hospitals & Clinics, The Sheraton Hotel, and housing units. The below-grade rail line that nce served the complex was transformed into the Midtown Greenway, a best-in-the-nation bicycle trail that now runs along the length of Lake Street, connecting users to local destinations and regional trails.

The investment in the Blue Line light rail connected Lake Street to prominent destinations in the metro area. Right below the Lake Street station, Corcoran Neighborhood Organization founded the Midtown Farmers Market, transforming a five-acre parking lot into a community hub, and eventually inspiring the development of a Hennepin County Service Center and over 500 units of housing.

These changes also brought challenges. The majority of Lake Street was reconstructed in the mid-2000s, and while the finished product offered new amenities and services that made Lake Street more pleasant to drive and walk along, the long period of construction created many obstacles for businesses, causing some to permanently close while others survived. In 2020, Lake Street businesses near 35W face the same challenges as the area undergoes major construction.

Still, Lake Street continues to change and evolve, led by community members who make it their home. Many East African entrepreneurs have brought new investment by launching businesses like Safari Express, Juba Graphics, Seward Pharmacy, and the many small enterprises located within Karmel Mall. The Somali Museum of Minnesota makes Somali history, culture, and stories available to all. Major new investments are planned for the area, including the closure of Kmart and the re-opening of Nicollet Ave and a series of new Bus Rapid Transit systems.

And as always, Lake Street will continue to welcome new people and be shaped by their contributions.